요한 베르누이와 최속강하선 도전

변분법 분야 만들어서 하루만에 풀었다

확실히 천재

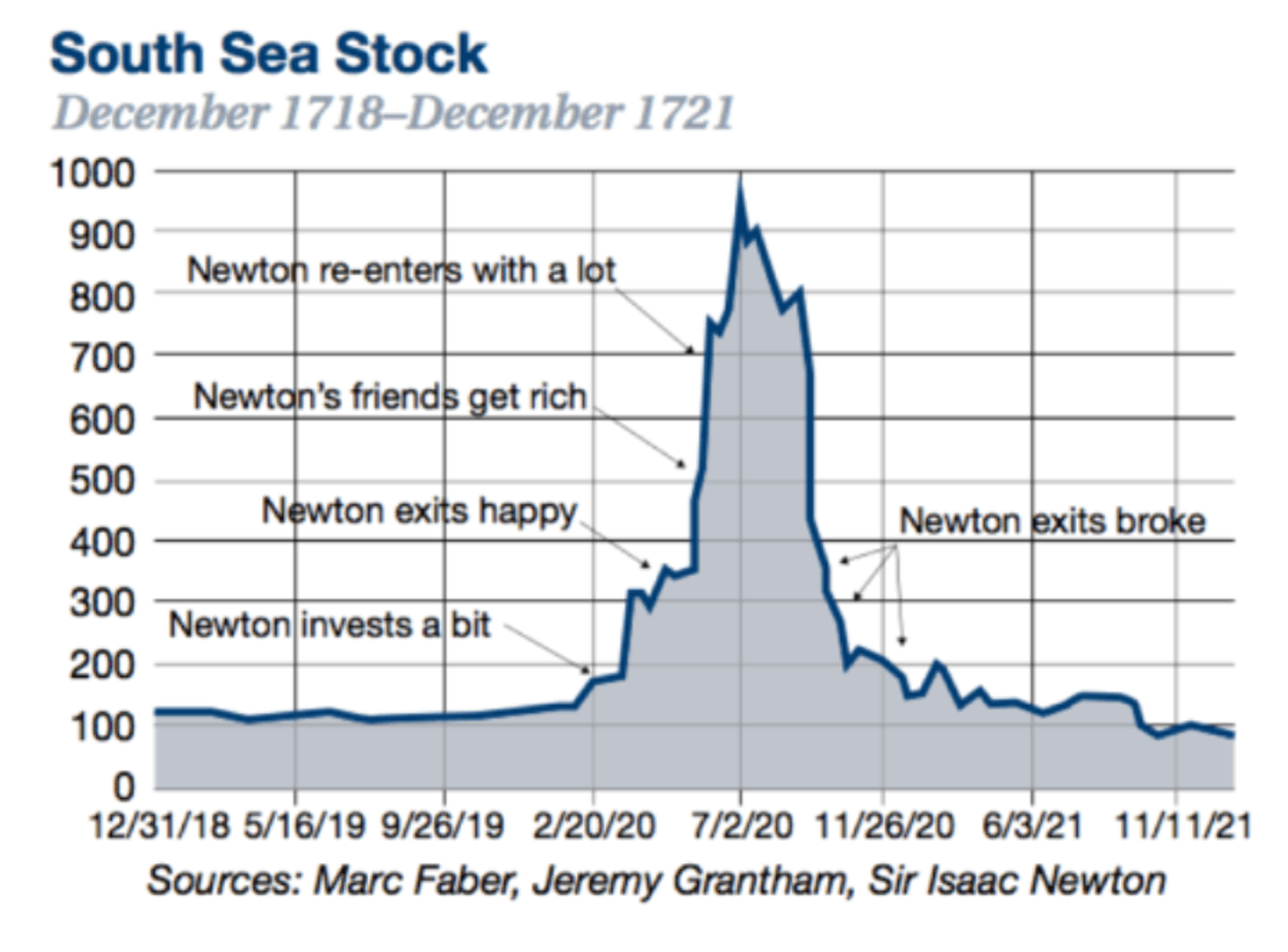

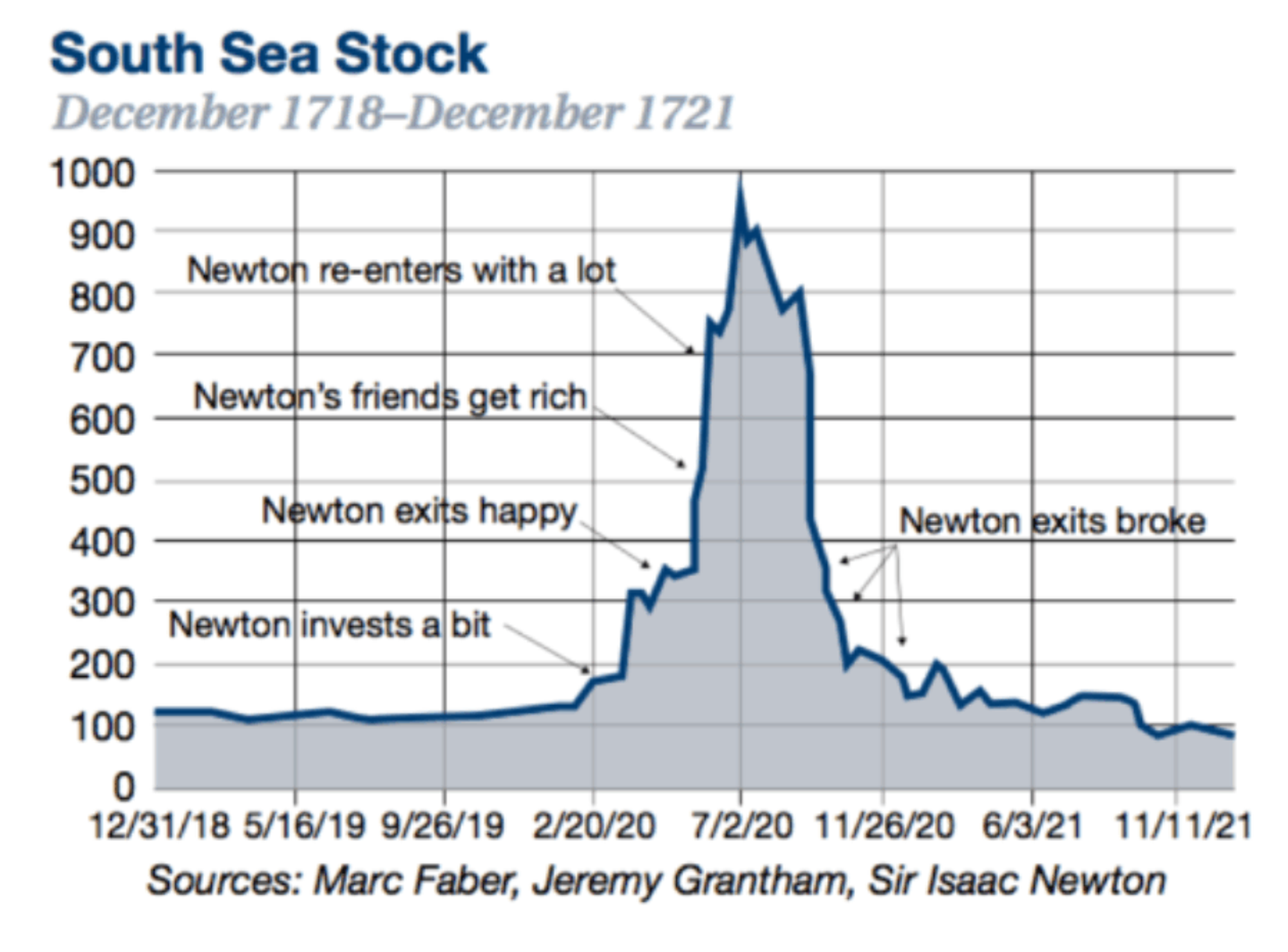

주식은 폭망

MacroView: Newton, Physics And The Market Bubble

Historically, all market crashes have been the result of things unrelated to valuation levels.

https://seekingalpha.com/article/4375276-macroview-newton-physics-and-market-bubble

28) South Seas Bubble of 1720: the First Major Manipulation of Financial Markets

Notes for Economics

www.saseassociates.com

Next, we will look at the British crisis known

as the South Seas Bubble, a crisis that stands

as the first major manipulation of financial

markets. Until the Crash of 1929, this bubble

endured as the classic example of opportunistic

self-enhancement.

The South Seas Company was formed by Parliament

as a British trade concession in 1711. This

was a monopoly for areas of the Pacific that

were under British rule. The company was a

startup firm with no sales and no earnings,

only with great prospects. The real prospects

centered on market manipulation and insider

trading.

In the early eighteenth century, Britain had

entered its period of imperial prosperity.

However, stock ownership remained a matter

of privilege that was limited mostly to the

aristocracy. Furthermore, women could not

inherit land, although females could own stock

at that time. A pent-up demand for stock developed

because of wide accessibility along with the

added benefit that dividends that were paid

out of profits went untaxed.

Parliament granted the enterprise a monopoly

concession along with loaned capitalization

of ₤10 million pounds sterling. Publicly

unknown at the time, members of Parliament

had bought capitalization bonds for South

Seas at ₤55. Once the company went public,

these investors exchanged each unit for ₤100

of stock in the South Seas Company.

However, its inexperienced directors quickly

entered into the slave trade, a venture at

which they failed. South Seas maintained its

stock price in the market despite this misfortune

as well as a war with Spain, shipments of

goods that were misrouted and lost, and bonuses

paid to the directors in a form that diluted

the value of shares.

Nevertheless, the situation improved in 1719.

Britain signed the Peace of Utrecht, a treaty

with Spain that enabled British trade with

Mexico. Given this newfound prosperity, the

directors of South Seas offered to fund the

entire British national debt of ₤31 million.

Stock prices doubled.

Five days after the bill became law, South

Seas offered a new issue of stock at ₤300

per share. The company offered a second issue

at ₤400. This one rose to ₤550 per share

within a month. The directors offered yet

another at 10% down, with no payments for

one year. Share price continued to rise to

₤1,000. The feasibility of the scheme became

secondary as the Greater-Fool Theory took

over—speculators would purchase shares,

prices would rise, secondary buyers would

appear, and the speculators would profit in

the after-market.

In the summer of 1720, the directors liquidated

their own shares. The news of their divestiture

leaked out quickly. Share price collapsed

and a market panic ensued. The British government

narrowly averted the complete erosion of public

credit. In response to this threat, Parliament

passed the Bubble Act that forbade issuance

of stock certificates in any company.

In addition, Britain implemented other measures

in order to restore confidence. The government

confiscated the estates of company directors

in an attempt to remunerate South Seas Company

investors. Other propositions put forth in

Parliament included placing bankers in sacks

filled with snakes and throwing them into

the Thames River!

In summarizing this bubble, let us analyze

the events. First, there was a pent-up demand

for investment opportunities. Second, the

government sponsored a trade-concession monopoly.

Third, inexperienced management failed to

create any real value for the company. Fourth,

war and the entry of new competition exerted

external pressures on the firm. Fifth, graft

occurred, which involved members of Parliament

in an effort to pass legislation that was

advantageous to a private company. Sixth,

dilutive stock dividends and new (dilutive)

stock issues were sold on generous terms and

margins while insiders manipulated trading

that included the dumping of shares.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rfZ4OZNhAJ8

Seonglae Cho

Seonglae Cho